Should I Screen? Lung Cancer Screening Decision Aid

Background: This project is my first inter-department collaboration between the School of Information and the School of Public Health. The work allowed me to hone my research skills by applying different research methods to enhance an existing product for a population with limited resources and literacy.

My friend and colleague, Lisa Lau, approached me to see whether I could bring my expertise in user-centered design to improve a web-based decision aid that her team had developed. Under the mentorship of two faculty from both schools, I orchestrated the migration of the site to a university-owned web hosting to allow for full control and redesigned the architecture to enable the parallel development of feature and content. I led a participatory design study and triangulated data with other on-going studies to inform the design of this decision aid.

My role(s): Project Co-leader, Researcher, Developer, Volunteer Organizer, Supervisor

Collaborator(s): Dr. Yan Kwan Lau, Dr. Mark S. Ackerman, Dr. Rafael Meza

Motivation: Lung cancer is one of the leading causes of death. A screening technique using low-dose computed tomography (CT) was recently tested and recommended. However, the screening rate is low, particularly for communities with lower socioeconomic status and limited access to resources.

Problem Solving: I explored ways of designing a web-based decision aid to be more inclusive by working with Latinx and African American participants (N=38) from a low-resource community in Detroit, Michigan, USA.

I collaborated with public health researchers to conduct participatory design workshops with patients to envision a design that was attentive to patients' background and experience. To obtain health professionals' perspectives, I presented the findings to physicians who specialize in lung cancer screening. I then integrated their comments with evaluative feedback from focus groups to provide holistic design suggestions.

Participatory Design

17 African Americans and Latinx

Focus Group

21 African Americans

Initial Analysis

Expert Feedback

2 Physicians and 2 Community Partners

Design & Development (A/B Testing)

Outcomes: Through performing thematic analysis with my colleagues, I identified three design suggestions to augment existing content-based guidelines

- Incorporate everyday language: Patients need everyday language to convey a sense of relevance to sustain their engagement.

- Highlight the process nature of screening: A decision aid needs to bridge the gap between patients' understanding of the screening timeline and that of physicians.

- Introduce social learning environment: A decision aid could consider providing a non-judgemental social learning environment with peers, which was found beneficial by patients.

The outcomes of this project include a scholarly publication (link), and a multilingual web-based decision aid was created for English and Spanish speaking individuals around the world with 7 K weekly visits. In addition to maintaining and supporting the continued refinement (e.g., A/B Testing), I am currently leading the effort to incorporate these findings into the next version through mentoring undergrad research and organizing volunteers to integrate a third language, Traditional/Simplified Chinese (currently in preview).

Summary:

Date: 2017 ~ Present

Research and Design Strategy

Use Participatory Design Workshop for Stakeholders to Take an Active Role in Guiding Discussion for an Unfamiliar Subject

As lung cancer screening is not a familiar subject to most people, I chose to use participatory design workshops as our main method over other approaches such as interviews or focus groups. A participatory design workshop provides a format that allows participants to direct conversation among participants, contribute their design ideas into tangible artifacts, and iterate over their designs in a group setting. Using participatory design (PD) relieves participants from the burden of providing all the 'answers' during their conversation with the research investigators. Instead, PD creates an environment for participants to have a conversation with each other and document their ideas by creating visual presentations (e.g., sketches).

In addition to a formative study, we also invited our participants to provide direct evaluative feedback to the current design of a lung cancer screenign decision aid. As a result, my colleagues and I designed a three-stage study format: participatory design, focus group, and expert feedback.

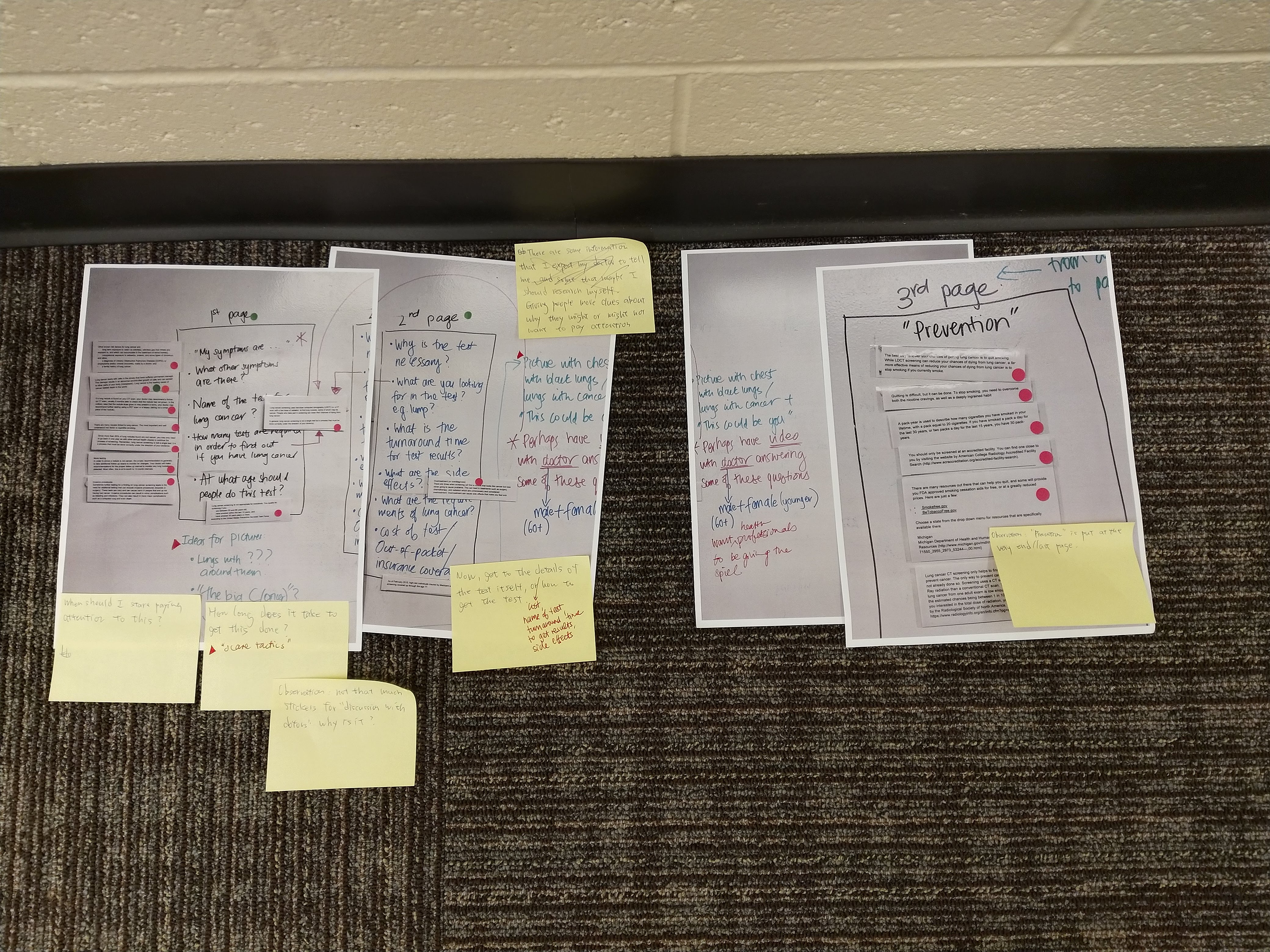

In each participatory design workshop, we invited participants to design a decision aid to help people, including themselves, to understand lung cancer screening. We provided a scenario where the participant assumed the role of 1) a potential patient or 2) a family member of a potential patient of lung cancer. We provided an initial prompt for participants, “What would you like to know about lung cancer screening?” and asked them to write down questions by themselves. Participants then worked in a group of 2 or 3 to design a website (or document) to answer the questions they raised. Participants were encouraged to illustrate their ideas on paper (e.g., sketches) and then to share with the rest of the session for feedback.

After participants generated their design, we provided paper cut-outs of the content on the current version of a lung cancer screening decision aid. Participants commented on whether they understood the content and whether they thought the content was useful. They were then invited to evaluate whether the content could be used in their own design by attaching the cut-outs to their design if appropriate.

Conduct Focus Group to Garner Comments and Feedback on Current Design

To obtain a more thorough view of the pros and cons of the current design, we conducted a series of focus groups to obtain evaluative feedback on the current version of the decision aid. Participants first browsed the current version in groups of 2 or 3 for 10 to 15 minutes. The research investigator then invited everyone to share their comments and feedback regarding whether the content and the presentation made sense, and attempted to identify the challenges that prevent patients from getting the full benefit of a decision aid.

Apply Thematic Analysis using Affinity Wall to Identify Key Perspectives from Intended Users

To synthesize what we were hearing from our participants, I worked with a public health researcher to perform thematic analysis on transcripts and design outcomes (i.e., sketches). We coded the data individually and then discussed with each other to iteratively identify themes on what the patients said about creating an inclusive decision aid for them.

Compare Participants and Physicians' Perspectives to Identify Missing Opportunities for Tools Designed to Support Shared-Decision Making

In addition to patients' views, it is important also to understand physicians' perspectives as patients will need to work with physicians throughout the screening process as part of the shared decision-making. My colleague and I conducted semi-structured interviews with two physicians who specialized in shared decision-making for lung cancer. During the interviews, we presented the emerging themes of patients' views as prompts for physicians to comment and reflect on their own experience working with patients. We compared and contrasted their views with that of patients, and identified gaps and opportunities for improvement to make the decision aid 1) more approachable for patients with lower general and health literacy and 2) more useful for facilitating patient-physician communication.

<figcaption style="text-align: center">

We iteratively grouped themes together that represent the challenges and design opportunities from the participatory design workshop and focus group data, and presented the emerging themes to physicians for feedback.

</figcaption>

</div>

<br />

Outcomes

Findings & Implications

We have identified three design opportunities to improve the inclusiveness of a lung cancer screening decision aid for a traditionally under-screened population: vocabulary, time, and delivery.

| Vocabulary |

|---|

|

| Time |

|---|

|

| Delivery |

|---|

|

For vocabulary, we found that patients needed everyday language and tone to convey a sense of relevancy and to make them comfortable continuing their engagement with the decision aid. Regarding time, we identified the difference between patients' perception of screening timeline and that of physicians. For instance, lung cancer screening is a process, but might often be mistaken as a one-off test for some patients. For delivery, we discovered that, while the screening decision itself might ultimately be individual, participants found that the process to explore and reach such a decision could be supported by a non-judgemental social learning environment with peers.

For more details, including concrete design recommendations, please refer to our PervasiveHealth 2019 paper listed below.

(diagram for the themes and key points)

</div>

<br />